Mountain Jews

джуһур Cuhuro | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 2004: 150,000–270,000 (estimated) 1970: 50,000–53,000 1959: 42,000–44,000 (estimated) 1941: 35,000 1926: 26,000 [1](estimated) 1897: 31,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 100,000–140,000 | |

| 22,000–50,000 [2] | |

| 10,000–40,000[3] | |

| 2,000 (2020)[4] | |

| 266 (2021)[5] | |

| 220 (2012)[6] | |

| Languages | |

| Hebrew, Judeo-Tat (Juhuri), English Azerbaijani, Russian, | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Persian Jews, Georgian Jews, Bukharan Jews, Mizrahi Jews, Soviet Jews, other Jewish ethnic divisions | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

Mountain Jews[a] are the Mizrahi Jewish subgroup of the eastern and northern Caucasus, mainly Azerbaijan, and various republics in the Russian Federation: Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan, Karachay-Cherkessia, and Kabardino-Balkaria, and are a branch of Persian Jewry.[8][9] Mountain Jews took shape as a community after Qajar Iran ceded the areas in which they lived to the Russian Empire as part of the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813.[10]

The forerunners of the Mountain Jewish community have inhabited Ancient Persia since the 5th century BCE. The language spoken by Mountain Jews, called Judeo-Tat, is an ancient Southwest Iranian language which integrates many elements of Ancient Hebrew.[11]

It is believed that Mountain Jews in Persia, as early as the 8th century BCE, continued to migrate east; settling in mountainous areas of the Caucasus. Mountain Jews survived numerous historical vicissitudes by settling in extremely remote and mountainous areas. They were known to be accomplished warriors and horseback riders.[12]

Mountain Jews are distinct from Georgian Jews of the Caucasus Mountains. The two groups are culturally differentiated: they speak different languages and have many differences in customs and culture.[13]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

Mountain Jews, or Jews of the Caucasus, have inhabited the Caucasus since the fifth century CE. Being the descendants of the Persian Jews of Iran, their migration from Persia proper to the Caucasus took place in the Sasanian era (224–651).[8] It is believed that they arrived in Persia from ancient Israel as early as the 8th century BCE.[14] Other sources attest that Mountain Jews were present in the region of Azerbaijan at least since 457 BCE.[15][16] However, Mountain Jews only took shape as a community after Qajar Iran ceded the areas in which they lived to the Russian Empire per the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813.[10]

Mountain Jews have an oral tradition, passed down from generation to generation, that they are descended from the Ten Lost Tribes exiled by the king of Assyria (Ashur), who ruled over northern Iraq from Mosul (across the Tigris River from the ancient city of Nineveh). The reference most likely is to Shalmaneser, the King of Assyria mentioned in II Kings 18:9–12.[citation needed] According to local Jewish tradition, some 19,000 Jews departed Jerusalem (used here as a generic term for the Land of Israel) and passed through Syria, Babylonia, and Persia and then, heading north, entered into Media.[citation needed]

Mountain Jews maintained a strong military tradition. For this reason, some historians[17] believe they may be descended from Jewish military colonists, settled by Parthian and Sassanid rulers in the Caucasus as frontier guards against nomadic incursions from the Pontic steppe.

A 2002 study by geneticist Dror Rosengarten found that the paternal haplotypes of Mountain Jews "were shared with other Jewish communities and were consistent with a Mediterranean origin."[17] In addition, Y-DNA testing of Mountain Jews has shown they have Y-DNA haplotypes related to those of other Jewish communities.[17] The Semitic origin of Mountain Jews is also evident in their culture and language.[17]

1600s–1800s: "The Jewish Valley"

[edit]By the early 17th century, Mountain Jews formed many small settlements throughout the mountain valleys of Dagestan.[18][unreliable source?] One valley, located 10 km south of Derbent, close to the shore of the Caspian Sea, was predominantly populated by Mountain Jews. Their Muslim neighbors called this area "Jewish Valley". The Jewish Valley grew to be a semi-independent Jewish state, with its spiritual and political center located in its largest settlement of Aba-Sava (1630–1800).[18] The valley prospered until the end of the 18th century, when its settlements were brutally destroyed in the war between Sheikh-Ali-Khan, who swore loyalty to the Russian Empire, and Surkhai-Khan, the ruler of Kumukh.[citation needed] Many Mountain Jews were slaughtered, with survivors escaping to Derbent where they received the protection of Fatali Khan, the ruler of Quba Khanate. [citation needed]

In Chechnya, Mountain Jews partially assimilated into Chechen society by forming a Jewish teip, the Zhugtii.[19] In Chechen society, ethnic minorities residing in areas demographically dominated by Chechens have the option of forming a teip in order to properly participate in the developments of Chechen society such as making alliances and gaining representation in the Mekhk Khell, a supreme ethnonational council that is occasionally compared to a parliament.[20] Teips of minority-origin have also been made by ethnic Poles, Germans, Georgians, Armenians, Kumyks, Russians, Kalmyks, Circassians, Andis, Avars, Dargins, Laks, Persians, Arabs, Ukrainians and Nogais,[19][21] with the German teip having been formed as recently as the 1940s when Germans in Siberian exile living among Chechens assimilated.[20]

Mountain Jews have also settled in the territory of modern Azerbaijan. The main Mountain Jewish settlement in Azerbaijan was and remains Qırmızı Qəsəbə, also called Jerusalem of the Caucasus.[22][23] In Russian, Qırmızı Qəsəbə was once called Еврейская Слобода (translit. Yevreyskaya Sloboda), "Jewish Village"; but during Soviet times it was renamed Красная Слобода (translit. Krasnaya Sloboda), "Red Village".[24]

In the 18th–19th centuries, Mountain Jews resettled from the highland to the coastal lowlands but carried the name "Mountain Jews" with them. In the villages (aouls), the Mountain Jews had settled in separate sections. In the lowland towns, they also lived in concentrated neighborhoods, but their dwellings did not differ from those of their neighbors. Mountain Jews retained the dress of the highlanders. They have continued to follow Jewish dietary laws and affirm their faith in family life.[citation needed]

In 1902, The New York Times reported that clans of Jewish origin, who maintain many of the customs and the principal forms of religious worship of their ancestors, were discovered in the remote regions of the Eastern Caucasus.[25]

Soviet times, Holocaust and modern history

[edit]

By 1926, more than 85% of Mountain Jews in Dagestan were already classed as urban. Mountain Jews were mainly concentrated in the cities of Makhachkala, Buynaksk, Derbent, Nalchik and Grozny in North Caucasus; and Quba and Baku in Azerbaijan.[26]

In the Second World War, some Mountain Jews settlements in North Caucasus, including parts of their area in Kabardino-Balkaria were occupied by the German Wehrmacht at the end of 1942. During this period, they killed several hundreds of Mountain Jews until the Germans retreated early 1943. On 19 August 1942, Germans killed 472 Mountain Jews near the village of Bogdanovka, and on September 20 the Germans killed 378 Jews in the village of Menzhinskoe.[27][28] A total of some 1000–1500 Mountain Jews were murdered during the Holocaust by bullets. Many Mountain Jews survived, however, because German troops did not reach all their areas; in addition, attempts succeeded to convince local German authorities that this group were "religious" but not "racial" Jews.[29][30]

The Soviet Army's advances in the area brought the Nalchik community under its protection.[31] The Mountain Jewish community of Nalchik was the largest Mountain Jewish community occupied by Nazis,[31] and the vast majority of the population has survived. With the help of their Kabardian neighbors, Mountain Jews of Nalchik convinced the local German authorities that they were Tats, the native people similar to other Caucasus Mountain peoples, not related to the ethnic Jews, who merely adopted Judaism.[31] The annihilation of the Mountain Jews was suspended, contingent on racial investigation.[29] Although the Nazis watched the village carefully, Rabbi Nachamil ben Hizkiyahu hid Sefer Torahs by burying them in a fake burial ceremony.[32] The city was liberated a few months later.[citation needed]

In 1944, the NKVD deported the entire Chechen populace that surrounded the Mountain Jews in Chechnya, and moved other ethnic groups into their homes; Mountain Jews mostly refused to take the homes of deported Chechens[33] while there are some reports of deported Chechens entrusting their homes to Jews in order to keep them safe.[34]

Given the marked changes in the 1990s following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and rise of nationalism in the region, many Mountain Jews permanently left their hometowns in the Caucasus and relocated to Moscow or abroad.[35] During the First Chechen War, many Mountain Jews left due to the Russian invasion and indiscriminate bombardment of civilian population by the Russian military.[36] Despite historically close relations between Jews and Chechens, many also suffered high rate of kidnappings and violence at the hands of armed ethnic Chechen gangs who ransomed their freedom to "Israel and the international Jewish community".[34] Many Mountain Jews emigrated to Israel or the United States.[37][38]

Today, Qırmızı Qəsəbə in Azerbaijan remains the biggest settlement of Mountain Jews in the world, with the current population over 3,000.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]While elsewhere in the Russian Empire, Jews were prohibited from owning land (excluding the Jews of Siberia and Central Asia), at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, Mountain Jews owned land and were farmers and gardeners, growing mainly grain. Their oldest occupation was rice-growing, but they also raised silkworms and cultivated tobacco and vineyards. Mountain Jews and their Christian Armenian neighbors were the main producers of wine, as Muslims were prohibited by their religion from producing or consuming alcohol. Judaism limited some types of meat consumption. Unlike their neighbors, the Jews raised few domestic animals, although tanning was their third most important economic activity after farming and gardening. At the end of the 19th century, 6% of Jews were engaged in this trade. Handicrafts and commerce were mostly practiced by Jews in towns.

The Soviet authorities bound the Mountain Jews to collective farms, but allowed them to continue their traditional cultivation of grapes, tobacco, and vegetables; and making wine. In practical terms, the Jews are no longer isolated from other ethnic groups.

With increasing urbanization and sovietization in progress, by the 1930s, a layer of intelligentsia began to form. By the late 1960s, academic professionals, such as pharmacists, medical doctors, and engineers, were common in the community. Mountain Jews worked in more professional positions than did Georgian Jews, though less than the Soviet Ashkenazi community, who were based in larger cities of Russia. A sizable number of Mountain Jews worked in the entertainment industry in Dagestan.[39] The republic's dancing ensemble "Lezginka" was led by Tankho Israilov, a Mountain Jew, from 1958 to 1979.[40][41]

Religion

[edit]

Mountain Jews are not Sephardim (from the Iberian Peninsula) nor Ashkenazim (from Central Europe) but rather of Persian Jewish origin, and most of them follow Edot HaMizrach customs. Mountain Jews tenaciously held to their religion throughout the centuries, developing their own unique traditions and religious practices.[42] Mountain Jewish traditions are infused with teachings of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism.[43] Mountain Jews have also developed and retained unique customs different from other Jews, such as govgil, an end-of-Passover picnic celebration involving the whole community.

Mountain Jews have traditionally maintained a two-tiered rabbinate, distinguishing between a rabbi and a dayan. "Rabbi" was a title given to religious leaders performing the functions of liturgical preachers (maggids) and cantors (hazzans) in synagogues ("nimaz"), teachers in Jewish schools (cheders), and shochets. The dayan was a chief rabbi of a town, presiding over beit dins and representing the highest religious authority for the town and nearby smaller settlements.[44] Dayans were elected democratically by community leaders.

The religious survival of the community was not without difficulties. In the prosperous days of the Jewish valley (roughly 1600-1800 CE), the spiritual center of Mountain Jews centered on the settlement of Aba-Sava.[18] Many works of religious significance were written in Aba-Sava. Here, Elisha ben Schmuel Ha-Katan wrote several of his piyyuts.[18] Theologian Gershon Lala ben Moshke Nakdi, who lived in Aba-Sava in 18th century, wrote a commentary on the Mishneh Torah of Maimonides. Rabbi Mattathia ben Shmuel ha-Kohen wrote his kabbalistic essay "Kol Hamevaser" in Aba-Sava.[18] With the brutal destruction of Aba-Sava in roughly 1800 CE, however, the religious center of Mountain Jews moved to Derbent.

Prominent rabbis of Mountain Jews in the nineteenth century included: Rabbi Gershom son of Rabbi Reuven of Qırmızı Qəsəbə, Shalom ben Melek of Temir-Khan-Shura (today known as Buynaksk), Chief Rabbi of Dagestan Jacob ben Isaac, and Rabbi Hizkiyahu ben Avraam of Nalchik, whose son, Rabbi Nahamiil ben Hizkiyahu, later played a crucial role in saving Nalchik's Jewish community from the Nazis.[23][45][46] In the early decades of the Soviet Union, the government took steps to suppress religion. Thus, in the 1930s, the Soviet Union closed synagogues belonging to Mountain Jews. The same procedures were implemented among other ethnicities and religions. Soviet authorities propagated the myth that Mountain Jews were not part of the world's Jewish people at all, but rather members of the Tat community that settled in the region.[43] Soviet antisemitic rhetoric was intensified during Khrushchev's rule. Some of the synagogues were later reopened in the 1940s. The closing of the synagogues in the 1930s was part of a communist ideology that resisted religion of any kind.[22]

At the beginning of the 1950s, there were synagogues in all major Mountain Jewish communities. By 1966, reportedly six synagogues remained;[26] some were confiscated by the Soviet authorities.[47] While Mountain Jews observed the rituals of circumcision, marriage and burial, as well as Jewish holidays,[48] other precepts of Jewish faith were observed less carefully.[26] Yet, the community's ethnic identity remained unshaken despite the Soviet efforts.[49] Cases of intermarriage with Muslims in Azerbaijan or Dagestan were rare as both groups practice endogamy.[50][51] After the fall of the Soviet Union, Mountain Jews experienced a significant religious revival, with increasing religious observance by members of the younger generation.[52]

Educational institutions, language, literature

[edit]

Mountain Jews speak Judeo-Tat, also called Juhuri, a form of Persian; it belongs to the southwestern group of the Iranian division of the Indo-European languages. Judeo-Tat has Semitic (Hebrew/Aramaic/Arabic) elements on all linguistic levels.[53] Among other Semitic elements, Judeo-Tat has the Hebrew sound "ayin" (ע), whereas no neighboring languages have it. Until the early Soviet period, the language was written with semi-cursive Hebrew alphabet. Later, Judeo-Tat books, newspapers, textbooks, and other materials were printed with a Latin alphabet and finally in Cyrillic, which is still most common today.[53] The first Judeo-Tat-language newspaper, Zakhmetkesh (Working People), was published in 1928 and operated until the second half of the twentieth century.[54]

Originally, only boys were educated through synagogue schools. Starting from the 1860s, many well-off families switched to home-schooling, hiring private tutors, who taught their sons not only Hebrew, but also Russian.[55] In the early 20th century, with advance of sovietization, Judeo-Tat became the language of instruction at newly founded elementary schools attended by both Mountain Jewish boys and girls. This policy continued until the beginning of World War II, when schools switched to Russian as the central government emphasized acquisition of Russian as the official language of the Soviet Union.

Mountain Jewish community has had notable figures in public health, education, culture, and art.[56]

In the 21st century, the Russian government started encouraging the revival of cultural life of minorities. In Dagestan and Kabardino-Balkaria, Judeo-Tat and Hebrew courses have been introduced in traditionally Mountain Jewish schools. In Dagestan, there is support for the revival of the Judeo-Tat-language theater and the publication of newspapers in that language.[56]

Culture

[edit]

Military tradition

[edit]

"And we, the Tats

We, Samson warriors,

Bar Kochba's heirs...

we went into battles

and bitterly, heroically

struggled for our freedom

-"The Song of the Mountain Jews"[57]

Mountain Jews have a military tradition and have been historically viewed as fierce warriors. Some historians suggest that the group traces its beginnings to Persian-Jewish soldiers who were stationed in the Caucasus by the Sasanian kings in the fifth or sixth century to protect the area from the onslaughts of the Huns and other nomadic invaders from the east.[58] Men were typically heavily armed and some slept without removing their weapons.[45]

Dress

[edit]

Over time the Mountain Jews adopted the dress of their Muslim neighbors. Men typically wore chokhas and covered their head with papakhas, many variations of which could symbolize the men's social status. Wealthier men's dress was adorned with many pieces of jewelry, including silver and gold-decorated weaponry, pins, chains, belts, or kisets (small purse used to hold tobacco or coins).[59] Women's dress was typically of simpler design in dark tones, made from silk, brocade, velvet, satin and later wool. They decorated the fabric with beads, gold pins or buttons, and silver gold-plated belts. Outside the house, both single and married women covered their hair with headscarves.[59]

Cuisine

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

Mountain Jewish cuisine absorbed typical dishes from various peoples of the Caucasus, Azerbaijani and Persian cuisine, adjusting some recipes to conform to the laws of kashrut, with a great emphasis on using rice (osh) to accompany many of their dishes. Typical Mountain Jewish dishes include:

- Chudu – A type of meat pie.

- Shashlik – skewered meat chunks, such as lamb chops or chicken wings.

- Dolma – vegetables such as grape leaves, onions, peppers, tomatoes and eggplants that are stuffed with minced meat, then boiled.

- Kurze or Dushpare – Dumplings that are boiled and then fried in oil on both sides until golden brown and crispy.

- Yarpagi – Cabbage leaves stuffed with meat and cooked with quince, lamb riblets and a sauce made of dried sour plums (alcha).

- Gitob

- Ingar – Square shaped dumpling soup with Meat (Chicken/Beef/Lamb), sometimes with tamarind paste added to the soup.

- Ingarpoli – Dumplings served with tomato paste flavored minced meat on top.

- Dem Turshi – Rice soup flavoured with garlic, dried mint and dried cherry plums.

- Tara – Mallow stew with pieces of meat, dried cherry plum, garlic, dill and clintaro. In Baku sometimes its made vegan with chestnuts instead of meat.

- Nermov or Gendumadush – Chicken or other meat stew with wheat and beans, traditionally cooked overnight from Friday to Saturday.

- Dapchunda Osh – Rice pilaf with lamb chunks, qazmaq and dried fruits such as raisin, apricots and golden plums.

- Osh Lobeyi – Rice pilaf with cowpeas and smoked fish.

- Osh Kyudu – Pumpkin Rice pilaf with carrots, pumpkin, qazmaq and dried fruits, traditionally served for Hannukah.

- Osh Mast – White rice with Mast, a variety of yogurt, on top.

- Shomo-Kofte bebeyi – Meatballs made from minced meat and onions cooked alongside potatoes, sometimes served on rice (osh).

- Buglame – (curry like stew of fish or chicken eaten with rice (osh).[60]

- Eshkene – Persian soup, made of Lamb, potatoes, onions, eggs, dried cherry plums, cinnamon and herbs such as cilantro, green onions, parsley and spinach, prepared for Passover.

- Yakhni Nisonui – The Derbendi variation of eshkene consist on lamb, potatoes, onions, eggs, dried cherry plums, cinnamon but without herbs, made on the first day of Passover.

- Yakhni Nakhuti – A soup made of lamb, chickpeas, potatoes and dried plums cooked in a tomato paste based soup. served with rice.

- Hoshalevo – (honey-based treats made with sunflower seeds or walnuts) typically prepared for Purim.

- Bischi – Fried dough topped with hot honey syrup, typically prepared for Purim.

- Hallegh – made with mixture of apples, walnuts, honey, raisins, cinnamon and wine, a ritual dish prepared for Passover.

- Pakhlava

- Fadi-shiri – A milk cake made of flour, eggs, butter, milk, sugar, turmeric, raisins, walnuts, sesame seeds and poppy seeds, served during Shavuot.

- Pertesh – A dish consist of a Lavash bread that is soaked in honey based syrup and filled with a milk porridge inside, served for Shavuot.

- Khashil – Sweet porridge made of flour, butter, honey, cinnamon and turmeric with a crunchy crust.

- Lovush Roghani

- Khashlama – Boiled chunks of meat, usually beef, veal, or lamb, as well as vegetables such as bell peppers, potatoes, tomatoes and onions, in hot water.

- Khoyagusht – Meat pie made of eggs, turmeric, slow cooked meat (usually sheep or goat) and its broth, often considered to be the "national dish" of the Mountain Jews.

- Khoyaghusht Kyargi – Khoyagusht with chicken instead of red meat.

- Khoyahusht Bodimjon – Khoyagusht with eggplants instead of meat, without turmeric.

- Nukhorush – Beef or Lamb cooked with quince, raisins, dried golden prunes, dried apricots, chestnuts and flavoured with turmeric, sometimes served alongside rice (osh).

- Nukhorush marjumeki – Lentil stew with potatoes, zucchini, onions, and carrots flavoured with cilantro, dill, cumin and turmeric.

- Gayle or Khayle – A dish made of herbs, onion and eggs.

- Dugovo – A soup made by cooking yogurt, with a little bit of rice, a variety of fresh herbs such as dill, mint, and coriander.

- Aragh – a strong alcoholic drink made of distilled fermented mulberry juice. It can be made from both black and white mulberries.

- Asido

- Harissa – A dish of Mountain Jews from the northern regions in Dagestan made of Meat, Potatoes and dried cherry plums cooked in tomato sauce, traditionally used in weddings.

Music

[edit]The music of Mountain Jews is mostly based in the standard liturgy, for prayer and the celebration of holidays. Celebratory music played during weddings and similar events is typically upbeat with various instruments to add layers to the sound.[61]

Notable Mountain Jews

[edit]- Omer Adam, Israeli singer

- Udi Adam, Israeli general[62]

- Yekutiel Adam (1927–1982), Former Deputy Chief of Staff of the Israeli Defense Forces[62]

- Albert Agarunov (1969–1992), Azerbaijani soldier[62]

- Yakov Agarunov (1907–1992), Soviet poet and playwright

- Ilya Anisimov (1862–1928), Russian ethnographer, ethnologist and engineer

- Astrix, producer of trance music

- Daniil Atnilov (1913–1968), Soviet poet

- Gyulboor Davydova (1892–1983), Soviet winegrower

- Hizgil Avshalumov (1913–2001), novelist, poet and playwright[63]

- Mishi Bakhshiev (1910–1972), Soviet writer and poet

- Manuvakh Dadashev (1913–1943), Soviet poet

- Mikhail Gavrilov (1926–2014), Soviet writer and poet

- Sarit Hadad, Israeli singer[64]

- Zarakh Iliev (born 1966) Russian businessman

- Gavril Abramovich Ilizarov (1921–1992), Soviet physician (Mountain Jewish father, Ashkenazi Jewish mother)[62]

- Telman Ismailov, businessman[65]

- Tankho Israelov (1917–1981), dancer, choreographer

- Sergey Izgiyayev (1922–1972), author, translator, and songwriter[66]

- Tamara Musakhanov (1924–2014), Soviet sculptor and ceramist

- Mushail Mushailov (1941–2007), Soviet/Russian artist and teacher

- God Nisanov, Russian businessman[67]

- German Zakharyayev (born 1971) – businessman, Vice-President of the Russian Jewish Congress[68]

- Gennady Simeonovich Osipov (1948–2020), Russian scientist and professor

- Iosif Prigozhin, Russian music producer

- Lior Refaelov, Israeli football player[62]

- Zoya Semenduyeva (1929–2020), Soviet and Israeli poet

- Robert Tiviaev, Israeli politician, former member of the Knesset[69][70]

- Israel Tsvaygenbaum, Russian-American artist (Ashkenazi Jewish father, Mountain Jewish mother)

- Yaffa Yarkoni (1925–2012), Israeli singer, winner of the Israel Prize in 1998 for Hebrew song [71]

- Anatoly Yagudaev (1935–2014), sculptor

- Zhasmin (née Sara Manakimova), Russian pop singer (2005)[72]

- Yekutiel Ravayev (1927–1982), Mountain Jewish man who immigrated to Eretz Israel during the Ottoman era.[73]

Gallery

[edit]-

Mountain Jewish delegates with Theodor Herzl at the First Zionist Congress, held in Basel, Switzerland (1897)

-

Mountain Jew c. 1898

-

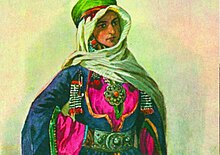

Mountain Jewish woman from Dagestan. 1870–1880.

-

Mountain Jewish woman and her children c. 1900

-

Mountain Jews of the Caucasus c. 1900

See also

[edit]- Mountain Jews in Israel

- Qırmızı Qəsəbə, the primary settlement of Azerbaijan's population of Mountain Jews (3600)

- History of the Jews in Azerbaijan

- History of the Jews in Buynaksk

- History of the Jews in Derbent

- History of the Jews in Makhachkala

- World Congress of Mountain Jews

- Museum of Mountain Jews

- Judaism in Dagestan

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also known as Caucasus Jews, Juhuro, Juvuro, Juhuri, Juwuri, Juhurim, or Kavkazi Jews, (Hebrew: יְהוּדֵי־קַוְקָז Yehudey Kavkaz or יְהוּדֵי־הֶהָרִים Yehudey he-Harim; [7] Azerbaijani: Dağ Yəhudiləri).

References

[edit]- ^ "The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire". www.eki.ee. Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Gancman, Lee. "A glimpse into Azerbaijan's hidden all-Jewish town". www.timesofisrael.com.

- ^ Habib Borjian and Daniel Kaufman, “Juhuri: from the Caucasus to New York City”, Special Issue: Middle Eastern Languages in Diasporic USA communities, in International Journal of Sociology of Language, issue edited by Maryam Borjian and Charles Häberl, issue 237, 2016, pp. 51-74. [1].

- ^ Shragge, Ben. "Canada's Mountain Jews". Hamilton Jewish News.

- ^ "All-Russian population census 2020". rosstat.gov.ru. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "In Wien leben rund 220 kaukasische Juden" (in German).

- ^ Brook, Kevin Alan (2006). The Jews of Khazaria (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 223. ISBN 978-1442203020.

The traditional language of the Mountain Jews, is part of the Iranian language family and contains many Hebrew elements. In Juhuri, they call themselves Juhuri (Derbent dialect) or Juwuri (Kuba dialect), and in Russian they are known as Gorskie Yevrey.

- ^ a b Brook, Kevin Alan (2006). The Jews of Khazaria (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 223. ISBN 978-1442203020.

The traditional language of the Mountain Jews, Juhuri, is part of the Iranian language family and contains many Hebrew elements. (...) In reality, the Mountain Jews primarily descend from Persian Jews who came to the Caucasus during the fifth and sixth centuries.

- ^ "Mountain Jews - Tablet Magazine – Jewish News and Politics, Jewish Arts and Culture, Jewish Life and Religion". Tablet Magazine. 26 August 2010. Retrieved 2015-12-27.

- ^ a b Shapira, Dan D.Y. (2010). "Caucasus (Mountain Jews)". In Norman A. Stillman (ed.). Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Brill Online.

The Mountain Jews are an Iranian-speaking community that took shape in the eastern and northern Caucasus after the areas in which they lived were annexed by Russia from Qajar Iran in 1812 and 1813.

- ^ "Mountain Jews: customs and daily life in the Caucasus, Leʼah Miḳdash-Shema", Liya Mikdash-Shamailov, Muzeʼon Yiśraʼel (Jerusalem), UPNE, 2002, page 17

- ^ Goluboff, Sascha (Mar 6, 2012). Jewish Russians: Upheavals in a Moscow Synagogue. University of Pennsylvania. p. 125. ISBN 978-0812202038.

- ^ Mountain Jews: customs and daily life in the Caucasus, Leʼah Miḳdash-Shemaʻʼilov, Liya Mikdash-Shamailov, Muzeʼon Yiśraʼel (Jerusalem), UPNE, 2002, page 9

- ^ Mountain Jews: customs and daily life in the Caucasus, Leʼah Miḳdash-Shemaʻʼilov, Liya Mikdash-Shamailov, Muzeʼon Yiśraʼel (Jerusalem), UPNE, 2002, page 19

- ^ Ezra 8:17

- ^ Grelot, “Notes d'onomastique sur les textes araméens d'Egypte,” Semitica 21, 1971, esp. pp. 101-17, noted by Rüdiger.

- ^ a b c d Rosengarten, D (2002). "Y Chromosome Haplotypes among Members of the Caucasus Jewish Communities". Ancient Biomolecules.

- ^ a b c d e "Еврейское поселение Аба-Сава, Блоги на сайте СТМЭГИ". Stmegi.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-17. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ a b Jaimoukha, Amjad. The Chechens: A Handbook. Page 276

- ^ a b Usmanov, Lyoma. "The Chechen Nation: A Portrait of Ethnical Features". 9 January 1999.

- ^ The Vainakh Taips: Yesterday and Today Archived 2017-08-07 at the Wayback Machine. 25 January 2005

- ^ a b "Visions of Azerbaijan Magazine ::: Islam and Secularism – the Azerbaijani Experience". Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Рабби Гершон Мизрахи – праведный раввин общины горских евреев". Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Schwartz, Bryan, Scattered Among the Nations, Visual Anthropology Press, 2015

- ^ "Jewish Colony Found in the Caucasus.; Strange Discovery Made by a Traveler in Remote Region of the Mountains -- Ancient Religious Customs Which Are Faithfully Followed -- The Customary Temperance in the Use of Liquor One Trait Which Is Missing". The New York Times. September 14, 1902. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c Pinkus, B., & Frankel, J. (1984). The Soviet Government and the Jews, 1948-1967: A Documented Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Bogdanovka". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "The Holocaust of the Mountain Jews". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ a b Yitzhak Arad, The Holocaust in the Soviet Union, Section "Mountain Jews", pp. 294-297

- ^ Kiril Feferman: "Nazi Germany and the Mountain Jews: Was There a Policy?", in: Richard D. Breitman (ed.): Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 21 Spring 2007, Oxford University Press, pp. 96-114.

- ^ a b c "Горские евреи — жертвы Холокоста - Горские евреи. История, этнография, культура". Istok.ru. Archived from the original on 2015-04-06. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ Дима Мордэхай Раханаев (2012-09-19). "Рабби Нахамиль, Автор статьи Дима Мордэхай Раханаев, Новости горских евреев". Stmegi.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-12. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ Rouslan Isacov, Kavkaz Center 01.02.2005

- ^ a b JTA. (2000). Around the Jewish World: "Russia’s Mountain Jews Support War in Chechnya, but Are Eager to Get Out." Accessed November 12, 2013.

- ^ Gorodetsky, L. (2001). "Jews from the Caucasus: A dying breed?" Accessed November 12, 2013.

- ^ American Jewish Year Book, 1998, page 14.

- ^ Sarah Marcus, "Mountain Jews: A New Read on Jewish Life", Tablet Magazine, Accessed November 12, 2013.

- ^ Brown, F. (2002). "Mountain Jews struggle to keep culture intact", Chicago Tribune, 22 November 2002. Accessed November 12, 2013

- ^ Pinkus, B., & Frankel, J. (1984). The Soviet Government and the Jews, 1948-1967: A Documented Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chicago

- ^ "Еврейский архитектор ЛЕЗГИНКИ". Горские Евреи JUHURO.COM. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "ИЗРАИЛОВ Танхо Селимович". Словари и энциклопедии на Академике. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ Cnaan Liphshiz. (2013). "Jewish shtetl in Azerbaijan survives amid Muslim majority." Accessed at November 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Miḳdash-Shemaʻʼilov, L. (2002). Mountain Jews: Customs and Daily Life in the Caucasus (Vol. 474). UPNE. Chicago

- ^ "горские евреи. Электронная еврейская энциклопедия". Eleven.co.il. 2006-07-04. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ a b "DAGHESTAN - JewishEncyclopedia.com". Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Рабби Нахамиль, Автор статьи Дима Мордэхай Раханаев, Новости горских евреев". Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ Jewish Virtual History Library, Azerbaijan, Accessed November 11, 2013.

- ^ Cnaan Liphshiz. (2013). "Jewish shtetl in Azerbaijan survives amid Muslim majority." Accessed November 12, 2013

- ^ Headapohl, Jackie (15 August 2012). "Jews Who Cruise | The Detroit Jewish News".

- ^ Alexander Murinson. "Jews in Azerbaijan: a History Spanning Three Millennia." Accessed November 12, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Behar, D. M., Metspalu, E., Kivisild, T., Rosset, S., Tzur, S., Hadid, Y., ... & Skorecki, K. (2008). "Counting the Founders: The Matrilineal Genetic Ancestry of the Jewish Diaspora", PLOS One, 3(4), e2062.

- ^ BRYAN SCHWARTZ. "Teens lead Azerbaijan Jews up the spiritual mountain.", JWeekly Accessed November 12, 2013.

- ^ a b "Juhuri - Endangered Language Alliance". Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Горско-еврейские газеты советского периода, Автор статьи Хана Рафаэль, Новости горских евреев". Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Горские евреи в русской школе - Горские евреи. История, этнография, культура". Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Mountain Jews". Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ p. 158 The Mountain Jews of Daghestan, Jewish Communities in Exotic Places by Ken Blady (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson Inc., 2000)

- ^ Blady (2000), The Mountain Jews of Daghestan, pp. 158-159

- ^ a b "Национальная одежда и украшения горских евреев". DataLife Engine. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Чуду - горские пироги - The Jewish Times". The Jewish Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "The Music of the Mountain Jews - Jewish Music Research Centre". www.jewish-music.huji.ac.il. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Mountain Jews of Azerbaijan and Dagestan, Новости горских евреев". Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Good name is very valuable thing." From interview of his daughter Lyudmila Hizgilovna Avshalumov. Retrieved 08.06.2011.

- ^ "Сарит Хадад". Горские Евреи JUHURO.COM. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "It's an all-Jewish town, but no, it's not in Israel - The Jewish Chronicle". Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Воспоминания об отце". Горские Евреи JUHURO.COM. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Официальное опубликование правовых актов в электронном виде". Pravo.gov.ru:8080. 2014-01-14. Archived from the original on 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ "German Zakharyaev: "I overcome obstacles and sadness in life over praying to God"". Jewish Business News. 24 December 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ "Knesset Members - Robert Tiviaev". www.knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ "Knesset Members". www.knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ "Yaffa Yarkoni - Jewish Women's Archive". Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Zhasmin". IMDb. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ "Fallen Heros, Yekutiel Ravayev". www.izkor.gov.il. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

Further reading

[edit]- Shapira, Dan D.Y. (2010). "Caucasus (Mountain Jews)". In Norman A. Stillman (ed.). Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Brill Online.

External links

[edit]- juhuro.com, website created by Vadim Alhasov in 2001. Daily updates reflect the life of Mountain Jewish (juhuro) community around the globe.

- newfront.us, New Frontier is a monthly Mountain Jewish newspaper, founded in 2003. International circulation via its web site.

- keshev-k.com, Israeli website of Mountain Jews

- gorskie.ru, Mountain Jews, website in Russian language

- "Judæo-Tat", Ethnologue